Is this thing still on? (More to come…)

The Real McCrea

John McCrea on the exponential wiring up of humanity

Letting Google’s AI dream in 3D

I’m a big fan of Google’s trippy explorations at the intersection of photography and artificial intelligence via the DeepDream neural network software, and I’m a longtime enthusiast of virtual reality. Recently, I wondered what might happen if I connected these two interests.

Fortunately, my friends Joseph Smarr of Google and Chris Lamb of NVIDIA had recently helped our mutual friend and professional photographer Dan Ambrosi overcome the technical hurdles to apply DeepDreaming to his multi-hundred megapixel panoramic photos, with some pretty stunning results. Might they be willing to run a few of my Photospheres through their highly scalable, cloud-based DeepDreaming instance? Indeed, they were.

The first Photosphere we put through the process was something I captured during a photoshoot for the homepage of my new startup, Parietal VR. We chose to let the neural networks go full “animalistic,” so the forest scene got fully populated with a nightmarish assortment of creatures. Here’s the Photosphere as a 2D projection, before and after DeepDreaming:

If you’d like to see it in 3D in your browser, I uploaded the processed Photosphere to VRCHIVE. But if you’re on Android and have the Cardboard demo app and a Google Cardboard, you should save the image to your phone and check it out in stereoscopic 3D.

[Note: For the Cardboard demo app to recognize it as a Photosphere, you may need to edit the filename to change “pano” to “PANO”. WordPress decapitalized it upon upload.]

For our second “dream sphere” we decided to veer away from animalistic in favor of more abstract, using a Photosphere I shot of an outdoor sculpture in Palo Alto, made from willow branches, “Double Take” by Patrick Daugherty. Here’s the 2D projection of the source Photosphere before and after processing:

The transformation is much more subtle, at least at this scale. But check out a small section:

And it’s way better in 3D, as you can imagine. Check it out on VRCHIVE. Or, as above, save to your phone and experience in Google Cardboard.

Note: For those curious, I captured these Photospheres with Google’s Camera app for Android on a Samsung Galaxy S6.

When Virtual Reality was First the Next Big Thing

The hype around virtual reality is now at an all-time peak, and with good reason. Thanks to Moore’s Law and the passage of a few decades, virtual reality is finally here (or just months away, depending upon where you draw the line on what is or is not truly virtual reality). But this is hardly the first time that virtual reality has been the super-hot Next Big Thing…

In fact, exactly 26 years ago this week VR got its first mainstream “hype moment” via a front page article in the January 23, 1990 edition of the Wall Street Journal. In a lengthy, well-researched, and well-written piece, legendary WSJ staff reporter G. Pascal Zachary described the promising technology as nothing less than “electronic LSD”. As I wrote about in Virtual Reality Then and Now, that piece inspired me to seek out a demo of the tech upon my arrival to Silicon Valley in the fall of 1991, and helped set me on the path to becoming a virtual reality entrepreneur (now two times over). With the anniversary of its publication just days away, I recently decided to dig up that historic article and re-share it with the world.

Alas, the online archive for the Wall Street Journal doesn’t go back that far, so I had to find another way. An online chat with a librarian at Stanford confirmed that they had a copy of the issue, so on a recent morning I headed over to campus and used my alumni status to gain entry to the Green Library.

Once inside, I asked where I could find the old newspaper collection. The nice folks behind the counter let me know that I was mistaken in my quest for hard copy. That morning I would not be flipping through yellowing pages of newsprint; the publication I sought was only available in the form of “microfilm” in the Media and Microtext Center, down in the basement.

Downstairs I was greeted by two friendly staffers who confirmed I was the guy they just were discussing on the phone, and that I was indeed seeking the WSJ microfilm from January 1990. A few minutes later, one of them emerged from the deep recesses of storage, carrying a single spool of film about three inches in diameter. He sat me down at one of many unoccupied microfilm viewing stations and started to give me a tutorial on how to use the equipment:

One of the many microfilm scanning stations in the basement of Stanford’s Green Library

After a minute or so of painfully arcane instruction, my aide stopped himself. “Actually,” he said, “how much of this are you planning to do?”

“Honestly,” I said, “I haven’t used microfilm in decades, and I don’t really anticipate doing it again any time soon. Maybe ever.”

And so he stopped his tutorial and kindly went about the cumbersome process of spooling the film back and forth to zero in on the edition in question. Fortunately, this “modern” microfilm machine was connected to a PC and had digital scanning capability. After a few minutes, we were able to resurface and digitally scan the front page, complete with the legendary “dot drawing” of the dreadlocked Jaron Lanier, founder/CEO of pioneering virtual reality startup, VPL:

Of course, just having a digital scan of the print edition doesn’t quite satisfy your, my, or anyone’s thirst for full-on digital access to the text, so over recent evenings I took on the painful task of “manual OCR”. [Hopefully, my friends at the Wall Street Journal will see this as “fair use” for posterity and not an infringement on their copyright.]

There’s so much I could say about this piece, starting with my surprise that it uses the term “artificial reality” throughout, despite VPL being widely credited with coining the term “virtual reality”. Also, note how much of modern Silicon Valley startup mythology is present: unconventional, visionary, “dropout computer whiz” founder/CEO with a disruptive technology that could impact many industries: “entertainment, education, engineering, medicine and many other fields of endeavor — pornography among them” — along with some rather prescient market timing doubts by a highly credible naysayer, no less than Jim Clark of Silicon Graphics (and later) Netscape fame.

So much more I could say, but here, without any more of my commentary, is the full text of this truly amazing intro of virtual reality to a mainstream audience:

Artificial Reality

Computer Simulations May One Day Provide Surreal Experiences

Jaron Lanier Develops Way For the User to Control and “Feel” Video Action

A Kind of Electronic LSD?

By G. Pascal Zachary, Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

REDWOOD CITY, Calif. — Jaron Lanier, his blond dreadlocks swaying, fiddles with the goggles on a young man’s head, then slips a black Lycra glove onto the subject’s right hand. The crowd that looks on is awaiting a glimpse of the future — the world of “artificial reality”.

“Just wave to get started,” instructs Mr. Lanier, a stocky six-footer who looks like a white rap-musician.

The crowd hears a sudden eruption of music and, on a video monitor, sees a bird flying high over a calm blue bay divided by a red bridge. The same vision to the man in the goggles seems eerily surreal. He is watching the bird through two screens mounted in the goggles. He feels as if he is part of the scene, which changes with a movement of his gloved hand: The bird soars then swoops down toward the water.

The crowd oohs and the young man giggles. Moments later, Mr. Lanier taps the subject’s shoulder. “Are you ready to enter the physical world” he asks. “Are you sure you’ll like it?”

To hear Mr. Lanier tell it, he himself wonders if artificial reality might be too appealing. He thinks of it as electronic LSD, with the power to blur a participant’s ability to distinguish between reality and fantasy. Advocates of the “Just Say No” persuasion, he says, may someday feel obliged to seek a ban on it. Timothy Leary, the former Harvard researcher who popularized LSD in the 1960s , says of artificial reality: “It’s getting closer and closer to the psychedelic experience.”

Mr. Lanier, a 29-year-old high-school dropout and computer whiz, is the most articulate and attention-grabbing member of a loose network of artificial-reality researchers and inventors. They have a vision of Americans working and playing in electronic fantasy world that, they say, will transform entertainment, education, engineering, medicine and many other fields of endeavor — pornography among them.

“This is far more important that the development of the personal computer,” contends Michael McGreevy, who oversees the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s work in artificial reality. “You’re not constrained by keyboards, ‘mice’ and monitors,” he says. “You can explore living environments.”

Wrung-Out Pilots

The crude artificial-reality machines that already exist are the product of years of research by the Air Force, NASA, and several universities and individuals such as Mr. Lanier, who is something of a maverick in the field. He is founder and chief executive officer of VPL Research Inc., a 16-person artificial reality firm here in Redwood City.

Even now, artificial worlds are in use. At Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, fighter pilots train in artificial cockpits. Outfitted with special goggles and headphones, they both see and hear the battle. “This really gets their juices flowing,” says Thomas Furness, until recently head of Wright-Patterson’s artificial reality project. “They come out of the cockpit sweating, wrung out.”

Architects and designers are on the verge of exploiting artificial reality. A University of North Carolina computer scientist has designed a program that allows architects to design a building and, after putting on the appropriate devices, lead a client on a tour of it. If the client wants larger windows in his office, the architect simply grabs the window with his electronically gloved hand and enlarges it. Many other projects are in the works.

First, Toys

In a modest way, Mattel Inc., the toy maker, brought artificial reality to the consumer market last fall. Mattel introduced a $90 computer glove, partly based on VPL’s design, that enables users to control some Nintendo games with hand gestures.

Dozens of companies in the U.S., Japan and Europe have purchased devices from Mr. Lanier’s firm, VPL Research Inc., to study ways to exploit the technology of artificial reality. Its unlimited potential for creating environments that a properly wired subject can see, feel and control explains all the interest. “This is probably the most powerful stimulant to the imagination ever,” says Brenda Laurel, a Los Gatos, Calif., computer consultant who has followed developments in artificial reality for a decade.

How does it work? Besides supplying computer-generated images, VPL’s goggls contain a magnetic tracking mechanism that responds to movements of a person’s head, causing the field of vision to shift as it might in the real world. Moving the glove signals the computer to move objects in the artificial environment.

Sensors stitched in the “data suit” can signal body movements by the wearer and change the visual perspective as if the wearer were moving through the scene. The sensing devices are connected by fiber-optic cables to computers that update the visuals 15 to 30 times a second. What the viewer sees is close to some sort of reality.

Still, today’s systems fall short of that. “I felt as if I were in a theater and could still see what’s going on backstage,” says Eric Hulteen, an engineer at Apple Computer, Inc. who has tried an artificial reality system developed by NASA. “The movement was slow, the images cartoonlike, and it was hard to grab anything. But I enjoyed it.”

Costly Trip

The hardware is expensive: $88,800 for a glove, $9,400 for goggles, up to $500,000 for a complete system — “a lot of money for a hit of acid,” quips Eric Lyons, director of technology for Autodesk, Inc., a Sausalio, Calif., concern developing artificial-reality software.

Mr. Lanier, artificial reality’s most extravagant promoter, was born in New York City and grew up in El Paso, Texas and Las Cruces, N.M. “Jaron was the noisiest infant in the nursery,” says his father, Ellery. “You could hear him through the glass windows.” In grade school he dressed so strangely — often wearing his shirts sideways, for example — that classmates once refused to allow him in a school photograph. As a teen-ager in New Mexico he lived with his widower father in a lean-to and, later, a geodesic dome. He kept a a herd of goats and milked them in the kitchen.

After dropping out of high school, Mr. Lanier faked his way into New Mexico State University. “He was a giant mind, one of the most brilliant students I’ve ever had,” recalls Warner Hutcherson, a professor of electronic music at the school. Yet he failed to get a degree. He also lacked social graces. “He smelled bad,” says Mr. Hutcherson. “But Jaron had other things to worry about than take a bath.”

As a corporate executive, Mr. Lanier has lost little of his eccentricity. Though neither a black nor a Rastfarian, he keeps his hair in dreadlocks that distinguish the Jamaican sect. He is apt to wear the same clothing for days. He drives a 1986 Citroen and lives in a rented four-room cottage at the end of an unpaved street in nearby Palo Alto.

World Without Limits

He is an accomplished musician and born performer. His place is cluttered with instruments. Many, like his Chinese harp and his Thai pipe organ, are exotic. Eleven wood flutes hang on one wall alone.

His obsession with artificial reality seems to reflect his dissatisfaction with conventional reality. “There’s this problem that you have to cope with [in] the real world,” he says. “You have to give up the infinity of your imagination to reach other people. Because we meet in this physical world, we have to make compromises, we have limited power. In [artificial worlds] there’s this incredible sense of release. All of a sudden you are infinite in this world.”

Mr. Lanier seized on artificial reality in 1983, after winning some notice as the creator of video games that blended sounds and scores into computer programs. On a visit to Atari, a video-game maker that was exploring new approaches in computer entertainment, he met Tom Zimmerman, a Massachusetts Institure of Technology graduate and also a musician, who had designed a computer glove in his spare time. They hit it off, and founded VPL in 1985.

One of the first things Mr. Lanier did with Mr. Zimmerman’s glove was to create a software program that enabled him to perform the music of the late guitarist Jimi Hendrix and another in which he conducted an orchestra. “Jaron’s dream is to make the experience of using a computer like playing music,” says Scott Kim, a software developer.

Manufacturing Chaos

Several VPL employees are enterprising artists with a knack for electronics. Ann Lasko chief designer of data suits, spends most of her free time doodling away at an artificial world in which she is a lobster (one of her biggest problems is to figure out the best way to move her antennae). Her husband, Young Harvil, who designed the firm’s three-dimensional program, has a master’s degree in fine arta and no formal training in computers. Before joining VPL, he was curator of a coprorate art collection.

As a workplace, VPL leans toward the chaotic. Mr. Lanier is no Henry Ford. The firm’s complex, custom-made products often aren’t finished until hours before shipment deadlines. The data suit in particular defies mass production. Unless it is fitted to its user with extreme care, its sensors fail to register properly. Some customers send wearers to VPL’s office so the suits can be tailored on them.

Yet customers as diverse as computer and amusement park developers are so excited about the prospect for artificial reality that they’re willing to endure Mr. Lanier’s dicey production schedules. “There’s something fundamentally right and interesting about what Lanier is doing,” says Jean-Louis Gassee, head of new products at Apple Computer, which has purchased several of VPL’s gloves.

Some customers, however, have soured on Mr. Lanier. ShareData Inc., a Chandler Ariz., software firm that financed VPL’s glove research in the mid-1980s, eventually became frustrated at Mr. Lanier’s inability to finish the job. Later it ran into unrelated financial problems that caused it to cancel the project.

Abrams/Gentile Entertainment, a New York toy design company, says it faced similar frustration after licensing VPL’s glove design. It then agreed to supply Mattel with a toy glove based on VPL’s technology. Abrams/Gentile says it spent $1.5 million developing VPL’s glove technology, but found “it wasn’t living up to its billing,” said Christopher Gentile, a principal in the firm. The company paid another design team to finish the glove, and is now seeking to deny VPL royalties on Mattel’s sales. VPL is fighting Abrams/Gentile’s move in court.

Playing With Toys?

Some have accused Mr. Lanier of taking credit for inventions made by others in an attempt to monopolize the essential technology of artificial reality.

VPL recently settled a lawsuit against Stanford University that, among other things, involved a dispute over the ownership of ideas. Howard Perlmutter, a Santa Cruz, Calif., inventor accuses Mr. Lanier of stealing his ideas about computer clothing. Mr. Lanier denies it. “People look at Jaron and think they can take advantage of himm” asserts Jack Russo, a specialist in intellectual property law whose clients include Mr. Lanier and Apple Comuter.

Others fault Mr. Lanier’s showmanship and says he is overselling artificial reality. “He’s bumbling around with toys,” says James Clark, chairman of Silicon Graphics Inc., maker of the high-speed graphics computers central to Mr. Lanier’s system. Mr. Clark thinks that computer goggles and clothing are too constraining, and won’t enter wide use.

Mr. Lanier disagrees, insisting he’s chosen the richest technical path toward artificial reality. “We’re certainly the pioneers of this field,” he asserts. In any case, he says, technical considerations are in a sense trivial when compared with the dream-fulfilling promise of artificial reality. He is eager to pursue it; asked how he plans to spend a weekend, he answers: “I’ll be busy. I’ve got some worlds to create.”

Mobile VR: The future’s so bright…

I had a great time up at GDC (the annual Game Developers Conference) in San Francisco yesterday. Two things are clear: virtual reality is finally arriving, and it’s future’s so bright, we’ll soon all be wearing shades:

[Image: Tipatat Chennavasin, Creative Director at Rothenberg Ventures’ VR Accelerator checks out a Mobile VR demo from MediaSpike at VR Mixer, a meetup hosted by SFVR and SVVR.]

[Image: Tipatat Chennavasin, Creative Director at Rothenberg Ventures’ VR Accelerator checks out a Mobile VR demo from MediaSpike at VR Mixer, a meetup hosted by SFVR and SVVR.]

A few takeaways from my visit to a very VR-centric GDC:

I and many others stood in line for hours for the hottest VR demos, like the Oculus “Crescent Bay” experiences at the Nvidia booth. The highlight was “Thief in the Shadows,” a collaboration between Weta Digital, Epic Games, and Oculus, which brought to life CG assets from “The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug”.

As amazing as it was, it and the other high-end demos, such as the one in support of the just-announced Vive VR headset from HTC and Valve (which I heard was truly awesome), showcase a major schism in the brewing VR platform wars. The most impressive demos require high-end (and often complex) hardware that will not be within the reach of mainstream consumers any time soon. For example, “Thief in the Shadows” showcased the power of Nvidia’s just announced Titan X graphics card, the “world’s most advanced GPU,” with 12 GB of RAM and no pricing yet announced. (Assume thousands of dollars.) These high-end demos also require placement of sensors around the room, which enables position tracking, but ups the complexity greatly.

On the other side of the schism is the “Mobile VR” camp, which embraces the smartphone as the core of the experience, severing the dependence on cables, high-end PCs or consoles, and external tracking sensor arrays. Leaders in this camp include Samsung, with Gear VR (developed in partnership with Oculus), and Google, with “Cardboard” (an open-source hardware approach to creating a display that ranges in price from cheap to free). Both are very exciting, and seem certain to bring VR to millions of consumers well in advance of the high-end folks. There’s a great article today in Wired by David Pierce, entitled The Future of Virtual Reality is Inside Your Smartphone. It suggests not only that Mobile VR will go mainstream first, but that it will also drive the future, thanks to ever more powerful smartphones:

More importantly, your next smartphone is going to be really, really powerful, and it’ll probably have a 4K or better screen. The one after that? Forget about it. Mobile computing is on such an insane trajectory, says [Samsung’s Nick] DiCarlo, that you’d be crazy not to just jump on the rocketship. “It’s pretty easy to draw these curves where [a smartphone] starts being better than Xbox 360,” he says, “better than all these things we’re accustomed to, really really quickly. Stuff that is relatively new, and the phone is going to be more powerful than that in one, two, three, five, ten years.” If that’s true, he says, and all evidence supports that it is, “what else would you do?”

We are witnessing the birth of a new platform, a new mass medium. As with the web in 1994/95 and mobile and social in 2007/08, there’s a Wild West, Gold Rush excitement and energy. It’s a great time to be in Silicon Valley, and with the intensity of the competition already underway, it will be an amazing time to be a consumer of virtual reality.

The launch of the first product line for web authoring and serving

[20 Years Ago, Part 15. Other options: prior post or start at the beginning.]

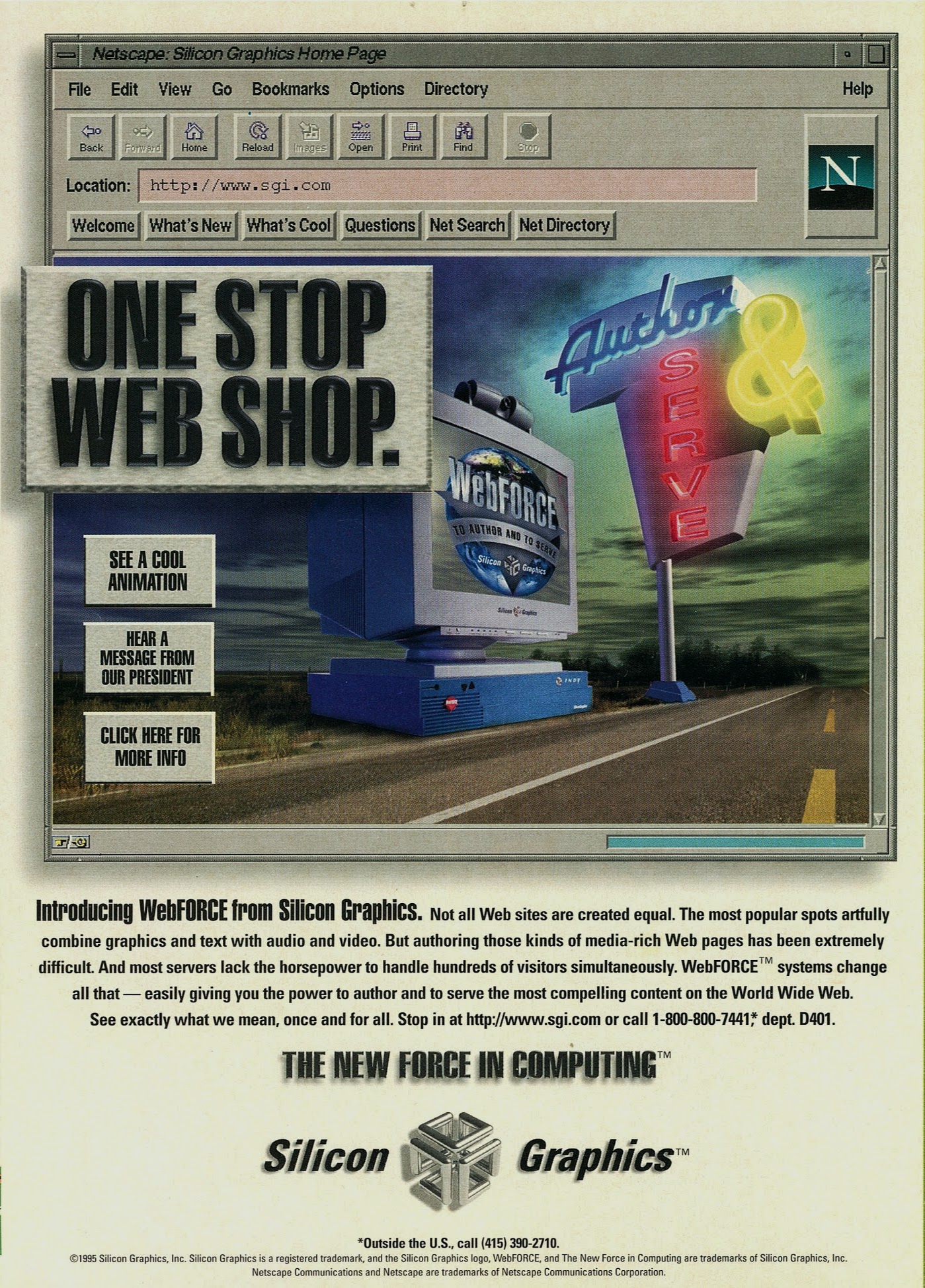

Somehow, against the odds, it all came together. WebFORCE went from funded project to new product line, ready for launch in just 76 days. Twenty years ago today, January 26, 1995, the two hottest companies in Silicon Valley at the time, Silicon Graphics (SGI) and Netscape, came together to launch the first turnkey solution for web authoring and web serving — the very first products with “web” in their name.

My instincts on timing proved correct. By launching in January, we caught all of our competitors totally off guard. In fact, it would turn out to be many months before Sun Microsystems, Apple, and Microsoft would begin to address the hot growth market of the World Wide Web. That secured a significant first-mover advantage for us, and made SGI the second hottest product brand in all of the web (behind our white hot new partner, Netscape).

And we didn’t just win from great timing. We hit the market “guns a blazing” with the unbeatable combination of killer product, a high-profile press event, an historic demo, a big budget ad campaign, and awesome collateral.

Killer Product (Even Microsoft Agreed!)

The WebMagic team burned the midnight oil and somehow managed to pull off the miracle of creating the first WYSIWYG HTML editor in under eight weeks. And under the technical leadership of David “Ciemo” Ciemiewicz and the product management leadership of Rob Lewis (one of my first hires), the WebFORCE software bundle expanded to include not just WebMagic and the Netscape server software, but many other essential tools for creating “media-rich web content”. Among those were a video tool called MovieMaker (with support for MPEG-1, QuickTime, and Cinepack) and an audio tool called SoundEditor (with support for AIFF, Sun/NeXT, and MS RIFF WAVE).

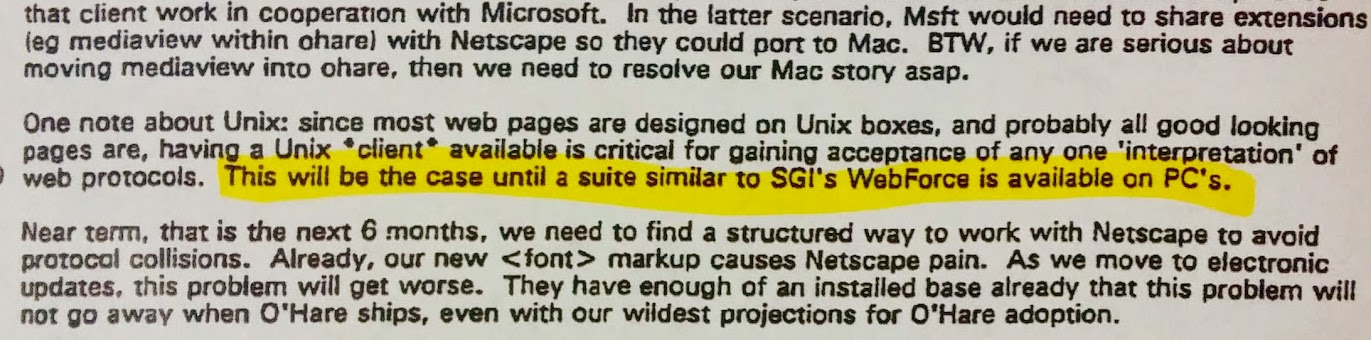

In terms of feature set, WebFORCE absolutely set the standard. Even five months later, it was referenced in a Microsoft internal exec team memo from Paul Maritz to Bill Gates, available online now because it was evidence in the U.S. Government’s anti-trust case against the company. In it, Maritz explains the gap between Unix and PCs in the web authoring space — and how it can’t be closed “until a suite similar to SGI’s WebFORCE is available on PC’s”:

High-Profile Press Event

SGI’s PR team, one of the best in the industry, pulled out all the stops. This news was clearly big enough that there was no need for pre-briefing. Instead, we would host an invite-only press event on our campus in Mountain View. In addition to the newsworthiness of an SGI product launch, we also had the big draw of the announcement of a partnership with Netscape, with Marc Andreessen agreeing to speak and do interviews.

I think we drew well over a dozen technology and business reporters. Alas, very little of the coverage we got is findable today online. Carl Furry, who was the lead from the PR team for this launch, did find this scanned piece with ComputerWorld’s coverage of the news while we compared our memories in recent days.

Historic Demo

Of course, no SGI press event would be complete without a 3D demo. Fortunately, weeks earlier, Rikk Carey, a charismatic director of engineering from the Visual Magic Division, had reached out to get me excited about a futuristic project his team had just gotten involved with, something called Virtual Reality Modeling Language (“VRML” for short). Though it was a very early-stage, grass-roots, open standard effort, I immediately saw it as an important missing piece of the WebFORCE puzzle. With the promise of bringing 3D to the web, VRML was a natural technology for SGI, the pioneer and leader in 3D computing, to embrace.

The WebFORCE launch was the first day that VRML was demoed to the press. I’m not sure what we actually demoed, but it would have been using our Open Inventor toolkit. And even though neither Marc Andreessen nor I now remember it, the ComputerWorld article linked to above says that in addition to our demo, Marc announced that Netscape Navigator 1.1 would “support transmission of three-dimensional graphics”.

Hard to believe now, but that demo and the mutual endorsement of SGI and Netscape for VRML would kickoff an industry-wide, multi-year wrestling match for control of 3D on the web. The battle would feature intense competition, awkward alliances, and multiple acquisitions. Along with SGI and Netscape, tech stalwarts Microsoft, Apple, Sun, and Sony would all become swept up in the mania. (Much more on that in future posts!)

Big Budget Ad Campaign

The team at Poppe Tyson, SGI’s ad agency of record, who had already blown me away by creating a killer logo for WebFORCE, did it again with what may be the very first print ads for any web product. The flagship ad, that ran for many months in publications like Wired, ComputerWorld, and since forgotten places like Interactive Age and Interactive Week, still looks great to me:

Two elements that I really love about “One Stop Web Shop” are that the primary visual is content framed within a web browser, and that the team really made this an SGI-quality ad, with multiple nods to 3D.

The secondary launch ad (shown at the top of this post) is in some ways even more remarkable. Using the web to actual sell stuff was unheard of at this point, with Amazon’s launch six months away. So for us to introduce WebFORCE as “the biggest revolution in commerce since the 800 number” was a pretty prescient claim! Readers of the Wall Street Journal got to see a full-page (but black & white) version of the ad within days of the announcement.

Over the first six months of 1995, we invested nearly $1 million to place these ads in the leading technology, business, and creative arts/new media publications. That, together with an amped up “Powered by Silicon Graphics” effort, made SGI appear to have already won the market, even before our first $10 million in sales.

Awesome Collateral

Amongst the earliest of hires to the WebFORCE team was Kris Hagerman, who like so many from the team would go on to found and lead other startups, including BigBook, the web’s first Yellow Pages, and Affinia, a Sequoia-backed e-commerce and digital advertising pioneer. If I were the “CEO” of WebFORCE (in practice, not actual title), Kris was my “COO”.

The very first thing Kris did after coming on board was take a project that was just a notion in my head, flesh it out, and see it to completion. The challenge was to create a brochure for the product line that looked and felt more like Wired magazine and less like a corporate data sheet. Here are some scans of this really beautiful “tri-fold”:

And a Cringe-Worthy (But Highly Effective) Sales Tool

Many of you may have seen those digitized VHS tapes from the early days of the web. Well, here’s one more!

In early 1995, SGI had a 1,000-person global direct sales force. They were really awesome at selling high-performance workstations, and were becoming more comfortable selling high-performance servers and super-computers. But they did not have any experience selling software or turnkey hardware/software bundles. And, like all salespeople everywhere, they had no experience selling web authoring and serving solutions.

So, to jump start sales, we created a 10 minute sales training tape, starring me, Rob Lewis and Ciemo, along with Steffen Low, product manager for the WebFORCE servers, and Gene Trent, applied engineering for the server side of the line. In it, we explained why the web was a hot new opportunity perfectly suited to SGI (in other words, why a sales person should focus on it, or in other, other words: $). We showcased key features and key differentiators, and, given the audience, we opened and closed the narrative with references to 3D.

Like any tape from the mid-’90’s, there’s a lot to cringe at here, whether it’s the less-than-professional readings from teleprompter or the cheesy music throughout. That said, this tape was instrumental in selling tens of millions of dollars worth of workstations and servers. It turns out that though this was clearly made with the sales team as the intended audience, many sales offices would actually show this directly to prospects. But with each successive viewing, the sellers got more and more comfortable with how to pitch the WebFORCE line.

Without further ado, here for the first time on the web is “WebFORCE: To Author and To Serve”:

And that is how we launched WebFORCE!

To be continued…

Minh Nguyen: The Co-Founder Who Wasn’t

A person relatively unknown until a few days ago has rocketed to infamy for (allegedly) walking into his ex-wife’s home last Thursday evening and shooting her new husband to death. While such an awful crime would, of course, make news, this particular story is getting enormous attention, running everywhere from CNN to TechCrunch – and even to People Magazine. Why such broad uptake?

Because the story is framed as the shocking and tragic fall of a highly successful tech entrepreneur “best known for co-founding Plaxo with billionaire Sean Parker”. There’s just one problem with that narrative: Minh Nguyen did not co-found Plaxo.

How would I know that?

I was Plaxo’s head of marketing (from 2006 through 2009), and I worked with and became good friends with the people who were there at the beginning of the company. And all of them agree that Minh was not a co-founder of the company.

Then, how do they remember Minh Nguyen?

Well, since Minh never set foot inside the doors of Plaxo, nor did a single day of work there, most of them, somewhat surprisingly, have actually never met him. To them, he’s just “that guy who keeps editing the Wikipedia page for Plaxo,” listing himself as co-founder, despite it not being true. Every attempt to set the record straight over the years has been met with a rapid re-edit by Minh.

Who are the actual co-founders of Plaxo?

On November 12, 2002, the company launched the beta version of its cloud-based address book service. In the last paragraph of the press release that went out on the wire that day, we can see that, “The company was founded by Sean Parker, also co-founder of Napster, and two Stanford engineers, Todd Masonis and Cameron Ring.” No Minh.

Why would Minh Nguyen claim to be a “co-founder of Plaxo”?

The best I’ve been able to piece together is that he and Sean may have talked about the idea of a smarter address book, and somehow in Minh’s mind that made him a co-founder. Here’s why that claim is wildly off the mark.

If the term “co-founder” is to have any meaning, the following must be true:

- The person has to actually be a part of the founding of the company. “Thoughts” or “talk” in the weeks or months before a company is founded are not sufficient; to be a co-founder, the person must participate in the actual founding of the company.

- By definition, co-founding is teamwork. If the other co-founders, for whatever reason, don’t agree that a person is a co-founder, that person is not. Simply put, there’s no such thing as a “lone wolf” co-founder.

- Becoming a co-founder takes an act of courage. A co-founder quits whatever else they’re doing, puts their reputation on the line, and goes all-in. A co-founder knowingly embraces the risk of failure of the new enterprise and their employment by it. There are no co-founders on the sidelines.

- Co-founding is not something you can do for just a few days or a few weeks. Genuine co-founders throw their heart and soul into the new venture, with the hope that years of hard work can create something great.

Minh’s claim to co-founder status for Plaxo fails on all counts:

- When the company that would be called Plaxo was formed by Sean, Todd, and Cam, Minh was not present. He played no role whatsoever in the creation of the company.

- The actual co-founders of Plaxo that I have spoken with on the topic have always definitively rejected the notion that Minh is a co-founder and expressed deep frustration at having to battle against his claim.

- Minh was not there when Sean, Todd, and Cam got turned down by one venture capital firm after another (in the post-Bubble “nuclear winter” of 2001). Minh was not there for the successful pitch to Sequoia Capital’s Mike Moritz. Minh was not there for the hard work of building the product, launching the service, and scrambling to rapidly scale up the operation. Simply put, he was never an employee of the company. (Not even for a single day.) His claim on LinkedIn to have worked there from January 2001 to October 2002 (screenshot below) is completely false.

Of course, it is possible that Minh may have been in some way a “muse” for Sean, and he may have even received a few shares in the company from Sean1. But there is one thing Minh never was: a co-founder of Plaxo.

As you can imagine, for everyone who did actually go “all in,” who took the risk and did the hard work to build Plaxo, seeing all of these disturbing news stories now about a murder supposedly committed by a “co-founder of Plaxo” (or in some headlines, just “Plaxo founder”) is quite troubling. We’re all getting emails from family, friends, and colleagues asking, “Did you know him?” And we’re all trying to explain the mystery of how, no, we actually don’t know who this guy is – or why or how he’s gotten away with his false claim for so long.

For even more on this story, I recommend Galen Moore’s well-researched piece in DCInno, entitled “Minh Nguyen Never Worked at Plaxo, Sources Say”. Among other things, it details Minh’s repeated editing of Wikipedia over the years.

In closing, I hope this post has added a small amount of clarity to a situation that is both confusing and terribly tragic. For all of us even remotely involved, our hearts go out to the survivors, the family of Minh’s ex-wife, Denise Mattison. For anyone who would like to help, please consider contributing to the Go Fund Me campaign for the Denise Mattison family.

1Not uncommon for outsiders to receive early shares from startups. For example, David Choe, a graffiti artist, was paid in stock by Sean Parker for spray-painting Facebook’s first office. Of course, that did not make him a co-founder (though it did make him rich).

WebFORCE: Creating the very first “web” brand

[20 Years Ago, Part 14. Other options: prior post or start at the beginning.]

Getting the product ready in time was only half of the challenge for our January launch. The other half was getting all of the marketing items done on deadline. And in 1995, that meant dealing with multi-week workflows to create and purchase print advertising and to design and produce print collateral and video sales tools.

And to really get started on any of those projects, it was vitally important to have locked down the “identity” of the product: its name, its tagline and fundamental positioning, and its logo or visual identity.

As those of you who have been following this series know, the project was pitched to the leadership of SGI with the name “Spider” and the tagline “Now making a web comes naturally”. In the weeks that followed, that positioning started to feel weak to me. While it had the benefit of obvious analogy, it lacked any sense of the strategic land grab that I intended for the project. Also it seemed more appropriate for a singular product, rather than a product line that spanned multiple configurations of workstations and servers.

The search for a more appropriate identity had a very clear center of gravity; the organizing principle of the entire effort was that the web was the most important thing in all of computing. The web was the Big Wave that everyone needed to pay attention to.

And yet, there was not a single product that had “web” in its name at that time.

So, each day in late November and the first week of December, I thought up different web-based names. On the morning of Tuesday, December 6, while showering before work, the winning name came to me, “WebFORCE”.

I was instantly 100% sold. Within 24 hours, all documents relating to the project bore the new name.

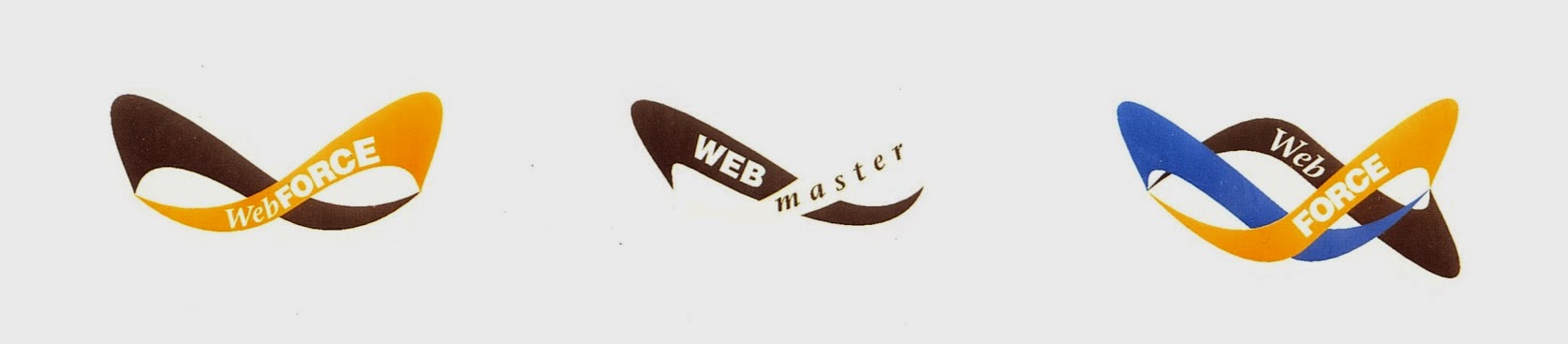

Now, the mad scramble was to turn that name into a logo that we could use in collateral and advertising. I turned to the crack team of designers in SGI’s marketing communications department. Within a couple days, they presented me with this array of logos:

WebFORCE was my first real product launch, so I was very much learning on the job. I didn’t have any experience choosing a logo, but I knew what I liked and what I didn’t. These might have been fine designs, but none of them was close to what I needed.

The problem, though I wasn’t consciously aware of it, was that I didn’t really need an actual “logo”. I was launching a product line, not a new company – and SGI already had an awesome 3D-based logo. What I needed was some sort of “visual identity” that could anchor the marketing. And getting to that would take a surprising route.

Part of what I liked about the name “WebFORCE” was that it seemed to fit really well with a messaging element that I had come up with a few weeks earlier, the phrase “To author and to serve.” It was inspired by the motto of the LAPD, which I knew from TV shows like Adam-12 and Dragnet, “To protect and to serve.”

“To author and to serve” fit WebFORCE so well, that within days it became the official tagline for the product line. And it would also serve as key inspiration for the design of the product line’s ultimate visual identity – from a team that wasn’t even tasked with designing it!

A major component of the WebFORCE launch was an aggressive million dollar print advertising campaign. As soon as the project was funded, I started frequent meetings with the ad agency that SGI had recently begun working with, Poppe Tyson.

At one of those, I must have mentioned that I was struggling a bit to get the right logo developed. To my surprise, the creative team at the agency proactively took on the challenge. The next meeting opened with a sort of “hope you don’t mind” intro. And then they showed me a big bold design they had developed for WebFORCE:

It certainly lacked the simplicity of a traditional corporate logo, but this was a visual identity worthy of the first “web” brand. It had the color and depth one would expect of Silicon Graphics (including its embrace of purple). And it had sufficient breadth and scale to encompass the SGI logo as a supporting (and central) element. In short, it seemed perfect then – and it holds up well 20 years later.

And now, we had all that we needed to get started on creating print ads, a brochure, data sheets, and a launch video. To be continued…

To Serve: How WebFORCE got its Netscape server software

[20 Years Ago, Part 13. Other options: prior post or start at the beginning.]

Having found a fortunate and just-in-time path forward on the authoring side of the WebFORCE1 project, it was time to focus on delivering the simpler, but equally vital, other half of the value proposition: web serving.

The approach seemed straightforward; instead of building our own software, like we were for authoring, for serving we would take the partnership route. We just needed to secure an OEM license with Netscape to bundle their recently released NetSite server software. But nailing down that “simple” deal would prove to be more difficult than I imagined for two reasons, one that was known to me at the time, and another that I would only figure out much later…

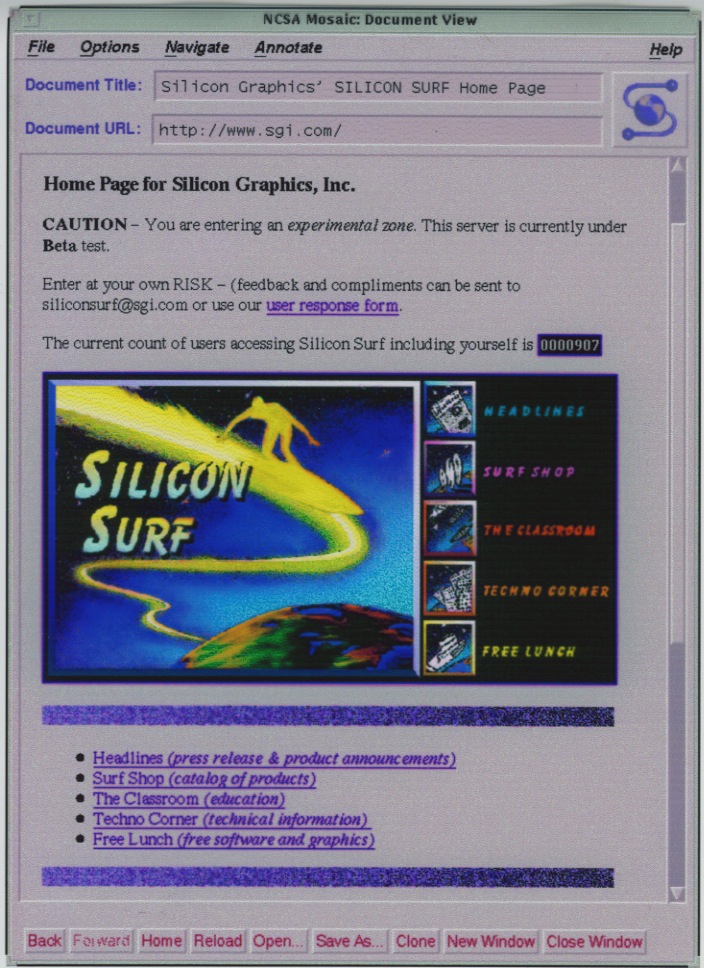

The complicating factor I was aware of was that in December 1994, SGI was already in the middle of a different OEM deal with Netscape. You see, our customer support team had more fully embraced the web than any other computer company at the time (and, arguably, more than any other company period), having launched a customer-facing portal called “Silicon Surf” in March of that year. Believe it or not, you can still interact with a live version of Silicon Surf from that period, thanks to the work of Daniel Rich, SGI’s “webmaster” back in ’94, who resurrected the site many years later from a promotional CD-ROM. (Yes, back then it actually made sense to distribute a website on a disk in order to get people excited to go online!)

By the way, when finding the screenshot of Silicon Surf below, I recently learned that it was the launch of SGI’s website that got the competitive juices flowing over at our rival, Sun Microsystems, leading to them to create the Sun.com website!

In the Fall of 1994, the team behind Silicon Surf, led by Kip Parent, had decided to do another thing no computer company had yet done – pre-install a web browser on every desktop, in order to make the web central to the support experience. So when I stepped in to negotiate on behalf of the WebFORCE effort, a single and simple OEM deal for the browser morphed into a two-part deal, with browsers for all SGI workstations and server software just for WebFORCE-branded configurations of workstations and servers.

Despite that complication, I was still expecting a quick and easy negotiation. After all, having the hottest company in Silicon Valley throw its weight aggressively behind the web, in general, and behind Netscape’s server and browser, in particular, would be a big win for Netscape. And given that our two companies were both founded by Jim Clark and that SGI was Netscape’s primary development and serving platform at the time, we seemed the most natural of partners. Why, we were practically family!

So, why shouldn’t we be able to put this deal together in just a few weeks? (And a few weeks was, indeed, all that I had.) The launch date was locked in: January 25. That meant I needed to close the Netscape deal by the end of December, or at the very least, the first week of January, in order to nail down all of the marketing materials.

My counterpart in the negotiation was Marc Matoza, who had recently joined Netscape as their first sales rep. I had naively assumed we would do a quick and friendly deal. In reality, the tone was far from “familial”. Making matters worse, Marc did not seem to share my sense of urgency. Quite the contrary, he seemed to view my deadline focus as a source of negotiating leverage. As the holidays approached, I knew I needed to take a different path.

In the technology business, it’s hard to understate the importance of right timing. I was truly fortunate not just to get into Stanford business school, but also to time it just right as a member of the class of ’93. As a result, I ended up riding out the recession in school and then entering Silicon Valley just as the web wave was beginning to swell. Many of the friendships I made at the GSB (in my class and in the class of ’94) formed the basis of an incredible network, touching almost every part of the emerging web industry. And one of those relationships in particular would come to play a pivotal role in getting me out of my negotiation quagmire.

There’s the people you know from classrooms and the people you know from parties. And then there’s people you know from playing hockey (or other sports). My fondest memories of Greg Sands, GSB class of ’94, are of getting schooled by him in how to translate my decent ice skating skills into playing rollerblade hockey. Even in a friendly game, hockey is pretty physical, but you don’t really want to check your business school buddies and send them tumbling to the blacktop. But Greg is a really great skater, having played on Harvard’s ice hockey team as an undergrad. So, I felt comfortable skating aggressively around him, even lightly checking him, knowing that it was way more likely that I would end up flat on my back than that he would. In short, we ended up getting to know, like, and really trust each other.

In Greg’s second year of business school, he spotted an interesting posting at the career center. Someone from the Stanford community was looking for a business school student to do some volunteer work on a startup business plan. The poster was none other than former electrical engineering professor Jim Clark, and the startup at that time was just Jim, Marc Andreessen, and the earliest seeds of what would eventually become Netscape. From that auspicious beginning, Greg would go on to become the company’s first business/marketing/product hire, coauthor of the business plan, and the person who gave the company its new name, Netscape, after the University of Illinois threatened to sue over the use of “Mosaic”. And now, he was the product manager of the very software products I so keenly wanted to license…

[Above: Greg and I in Stanford Business School Magazine, December 1995. Pretty clear we weren’t getting a lot of sleep that year!]

Greg and I met for coffee at Café Verona2 in downtown Palo Alto to talk it out. We didn’t do any actual negotiation. I shared my frustrations and my goals. And perhaps most important of all, I shared with Greg my “BATNA”. (That’s a term we both would have learned at the GSB in the negotiations class. It stands for “best alternative to a negotiated agreement”.) Although I was truly keen to bundle Netscape’s server software with WebFORCE, if for some reason we were unable to finalize a deal in time, I could live without it. In that case, we would emphasize our Web Magic authoring software and position the product line as Netscape-ready or add-your-own-server-software. This wasn’t a threat or posturing; I was just candidly sharing my situation.

Greg offered to see what he could do. Within days he broke the log jam. Terms became reasonable and the timeline radically accelerated. I ended up getting my deal well in advance of the holidays, and SGI became the second OEM licensee of Netscape. (The first OEM deal, struck a month earlier, was with Digital Equipment Corporation. That said, we would beat them to market, becoming the very first vendor of a turnkey web server.)

But what was it that had been the real friction? I didn’t ask, and Greg didn’t tell. But over time, I would come to understand that it wasn’t Marc Matoza dragging his feet. The real issue was Jim Clark, behind the scenes, who was still bitter about having been edged out3 of his own company. In my research for this blogpost, Greg recently shared with me that the WebFORCE deal “caused a bit of a firestorm internally, as Jim didn’t want SGI to get a special (and OEM prices always feel like specials).”

Special or not, I got my deal, and we were now on track to launch a kickass product on January 25, 1995, now about 40 days away!

To be continued…

1Though we had pitched the project to TJ as “Spider,” that was never really intended as the launch name. About two weeks after funding, I came up with the real name and tagline in the shower before work: “WebFORCE: To Author and To Serve”.

2It is now long since closed, but Caffe Verona played a role in Silicon Valley history – it was where Marc Andreessen first met Jim Clark.

3Jim resigned as Chairman of SGI, but only after years of strategic disagreement with our CEO, Ed McCracken, and a rising sense of being shut out of key decisions.

The Untold (and Rather Improbable) Story Behind the First Real HTML Editor

[20 Years Ago, Part 12. Other options: prior post or start at the beginning.]

The first mainstream and well-remembered “WYSIWYG”1 HTML editor, FrontPage, was released in October 1995. Less than three months later, the small startup that created it, Vermeer Technologies, was acquired by Microsoft for a whopping $133 million! FrontPage would become a key weapon for Microsoft in its ruthless, monopolistic “browser war” against Netscape.

But FrontPage was actually not the first WYSIWYG HTML editor; it was just the first one on Windows. A full year prior to Microsoft’s acquisition of Vermeer, Silicon Graphics, at the time the hottest company in Silicon Valley, launched a product called “WebMagic”. It was the actual first WYSIWYG HTML editor, empowering designers and business people for the first time to create web pages without learning to code HTML. This is the previously untold (and rather improbable) story of how that historic application came to be…

I’ll start the story from hours after I had secured $2.5 million in funding from Tom “TJ” Jermoluk, SGI’s President and COO, based on my pitch/commitment to launch a product line for web authoring and web serving by the end of January 1995. That deadline was less than 80 days away (a period that would include Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s!).

And that means that these events took place in the single craziest time of my career. It was such a blur, that I’m sure I’ll miss some key facts and miss-remember some details. With hope, others involved in the story will keep me honest.

I think it was in the afternoon of the day of the funding that Way Ting sought me out. He was the Vice President and General Manager of the Visual Magic Division (VMD) that created the desktop software environment and a bunch of tools to showcase the differentiation of our powerful workstations. And after the amazing events of the morning, he was keen to sign up for a critical element of the plan.

“We want to create that SGI-quality authoring tool you described,” he said.

“That’s great news,” I said.

“But there’s just one problem,” said Way. “The timeline is too short. I don’t think it’s possible to develop such a tool by the end of January. Any chance we can add a few weeks to the schedule?”

Way knew a heck of a lot more about software development than I did, but I had a deep conviction that timing was vital in this rapidly emerging web market. I feared that Sun or Apple were about to beat us to market with web authoring/serving solutions, and I strongly preferred to launch first with an imperfect product than to launch second or third with everything on my wishlist.

“I’m sorry, Way,” I said. “I know it’s crazy, and it may not be possible, but the one thing that is certain for this project is that we’re launching by the end of January.”

“Okay,” he said. “I’ll see what we can do.”

To my surprise, within a few days, he reached out to me again, asking if I’d accompany him to a meeting in Palo Alto with a company that had a possible solution to our problem. The company was Enterprise Integration Technologies (EIT), and although I didn’t know it at the time, it happened to be the startup that Marc Andreessen had moved to California for, and the one from which Jim Clark recruited him just months later to co-found what would become Netscape.

Our host for the meeting was EIT’s founder and CEO, Marty Tenenbaum, a more-than-a-little smart guy, with multiple degrees from M.I.T. and a PhD from Stanford. EIT was a pioneer in e-commerce, having conducted the very first Internet transaction in 1992. Therefore, it was not a surprise that nearly every desk had an SGI workstation on it. They were the real deal.

I have no idea how Way had managed to make this meeting happen, but it was pretty magical. What Marty showed us that sunny afternoon looked like exactly what I had been advocating for – an SGI-native web authoring system, with WYSIWYG HTML coding and an intuitive, drag-and-drop user interface. It looked pretty polished.

But when Way asked, “What is it written in?” Marty replied, “WINTERP.”

Ruh, roh!

I had never heard of that, and I’m guessing Way hadn’t either. Marty went on to explain that it was an interactive, object-oriented user interface language that EIT had developed.

As we drove back from the meeting, it became clear that this was hardly an ideal path for achieving our goal. I resolved to pursue my Plan B with fervor – getting SoftQuad to port their less-than-ideal alternative HTML editor, HoTMetaL Pro, as the candidate for bundling with our web workstations. It wasn’t WYSWYG, nor was it going exploit the differentiation of our OS and tools, but it could allow us to check-the-box for “HTML editor”.

But then, to my surprise, Way reached out to me a few days later with a proposal for another outing, this time to Sunnyvale, to the headquarters of Amdahl.

“Amdahl?” I thought. “Did I hear Way right? Why would we go visit such a freaking dinosaur?”

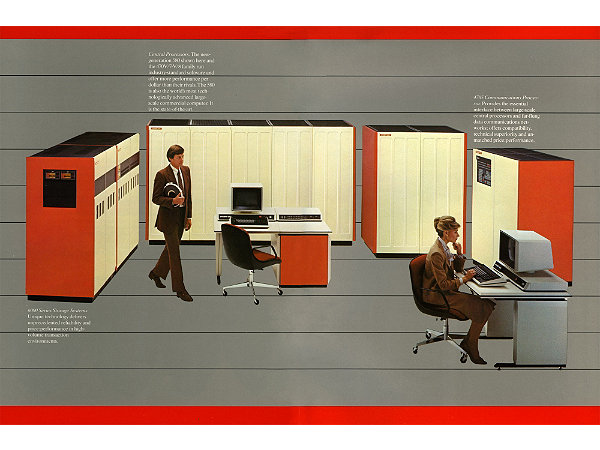

For my younger readers, Amdahl was a maker of IBM-compatible mainframe computers. Hardly the most likely place to find cutting-edge web software!

You may be thinking my story is old-timey, but here’s how ancient Amdahl looked to me 20 years ago:

Much to my surprise, what we found at Amdahl was a decent HTML editor, still under development by a single contractor developer, David Koblas. It was a Motif-based program, written in C++, running on Solaris. In short, it was exactly what we were looking for – the right kind of code base, far enough along in its development, that turning it into a robust SGI-native application just might be possible in weeks, not months.

Much to my surprise, what we found at Amdahl was a decent HTML editor, still under development by a single contractor developer, David Koblas. It was a Motif-based program, written in C++, running on Solaris. In short, it was exactly what we were looking for – the right kind of code base, far enough along in its development, that turning it into a robust SGI-native application just might be possible in weeks, not months.

I don’t know all the details, but within days we had struck a deal with Amdahl that somehow brought us both the code and David. In a recent email exchange, David recalls that to avoid creating a taxable event, no physical media were involved in the transfer of the source code; the bits were passed from Amdahl to SGI via FTP.

A small team was quickly assembled around David, including Ken Kershner (who managed the team), and Ashmeet Sidana, Baron Roberts, and Victor Riley. By then, I had locked in a launch date for the project: January 25, 1995. So this newly formed “WebMagic team” would have just under eight weeks to port to IRIX, integrate deeply with SGI’s desktop environment and media tools, and polish code that David now recalls as “quite buggy”.

In addition, the team fully embraced an even more audacious goal – full “render compatibility” with the now dominant browser, Netscape Navigator. And what that meant was aiming at a moving target. The team at Netscape was extending the capabilities of the browser at a blistering pace. The WebMagic team wanted to support it all, including tables, forms, and, yes, even the blink tag.

It took long days and nights, with David and Baron often working until 3:00am. (On those nights, they would typically switch to pair programming at 1:00am to minimize bugs.)

The heroic work of the team paid off. When we launched, WebMagic had become all that I and the team had hoped: a true WYSIWYG HTML editor with the polished look and feel of a word processor, drag-and-drop integration with SGI’s media toolkit, and pixel-perfect compatibility with Netscape Navigator.

And that is the rather improbable story of the creation of the very first WYSIWYG HTML editor.

But what of that “project” that WebMagic was such a central part of? To be continued…

1This is an old acronym for “What You See Is What You Get” which came into common use in the 1980’s during the word processing revolution. From Wikipedia “a WYSIWYG editor is a system in which content (text and graphics) onscreen during editing appears in a form closely corresponding to its appearance when printed or displayed as a finished product, which might be a printed document, web page, or slide presentation.”

How Google’s Carboard Will Take Virtual Reality Mainstream in 2015

I’ll admit that when I first heard of Google’s virtual reality headset that is both made of and named “Cardboard,” I thought it was a joke. Literally.

In fact, until I got one a week ago, I was pretty dismissive of the project/product, despite being a passionate fan of VR since the early ‘90’s!

Now that I’ve had a few days to play with Cardboard, I’m a convert. And an evangelist. In fact, I’m so into this contraption that I carry it with me almost everywhere I go. Why? Because it’s really a delight to see friends, family, and even strangers experience it for the first time.

Google’s Cardboard effort is radically accelerating the arrival of virtual reality as a mainstream medium. Yes, Oculus Rift will be a huge success, but it seems like the consumer edition won’t hit store shelves until either late 2015 – or even early 2016. And while Samsung is currently testing the waters with a limited, sold out release of an “Innovator Edition” of its very slick Gear VR offering, the consumer edition of the product is likely not coming until mid- to late-2015.

But Google’s Cardboard is here now. And it is supported by a companion app that’s already clocked over 500,000 downloads, a recently released SDK, a rapidly growing base of apps in Google’s Play Store (with new ones almost every day), and multiple “hardware” partners. Oh, and Google is adding support for VR across its product portfolio, starting with Google Earth, YouTube, and Google Camera (via the Photosphere feature), all part of the Cardboard app, and more recently with support in the Google Maps’ Street View. In short, Google is pursuing this aggressively as an ecosystem play.

[Above: An example Photosphere image via Google Camera.]

Sure, the plastic lenses (together with my need for reading glasses) make for an experience that is nowhere near as sharp as strapping on the Oculus Rift DK2. And the cardboard “headset” is pretty flimsy and leaks light. But the overall experience manages to cross over the believability threshold (while somehow avoiding the motion sickness problem), such that I can’t get enough of it, and everyone I show it to is blown away.

What apps get the best reaction? Flying around Google Earth is amazing. The virtual tour of the Palace of Versailles is really cool. Any of the roller coaster apps are sure to thrill. “Sisters” was spooky enough that my daughter couldn’t take it — and got an amazing scream out of my wife. And sitting on Paul McCartney’s piano on stage in Jaunt VR’s concert app thrilled my daughter. It was so believable, that when she saw the audience, she asked if they could see her!

Google Cardboard (together with the Google ecosystem) is making virtual reality a mass medium sooner than anyone expected. When a new mass medium is born (like the web in 1994 and 1995), great fortunes are up for grabs. And those who spot the trend and move early reap some of the greatest rewards.

So, what are you waiting for? The easiest, lowest cost way to be an early mover in virtual reality is to plunk down $15 to $25 to get yourself a cardboard headset. Oh, and they make a great Christmas present – not just for your techie friends and family, but for anyone who wants to be wowed by seeing the future a little early.