[20 Years Ago, Part 15. Other options: prior post or start at the beginning.]

Somehow, against the odds, it all came together. WebFORCE went from funded project to new product line, ready for launch in just 76 days. Twenty years ago today, January 26, 1995, the two hottest companies in Silicon Valley at the time, Silicon Graphics (SGI) and Netscape, came together to launch the first turnkey solution for web authoring and web serving — the very first products with “web” in their name.

My instincts on timing proved correct. By launching in January, we caught all of our competitors totally off guard. In fact, it would turn out to be many months before Sun Microsystems, Apple, and Microsoft would begin to address the hot growth market of the World Wide Web. That secured a significant first-mover advantage for us, and made SGI the second hottest product brand in all of the web (behind our white hot new partner, Netscape).

And we didn’t just win from great timing. We hit the market “guns a blazing” with the unbeatable combination of killer product, a high-profile press event, an historic demo, a big budget ad campaign, and awesome collateral.

Killer Product (Even Microsoft Agreed!)

The WebMagic team burned the midnight oil and somehow managed to pull off the miracle of creating the first WYSIWYG HTML editor in under eight weeks. And under the technical leadership of David “Ciemo” Ciemiewicz and the product management leadership of Rob Lewis (one of my first hires), the WebFORCE software bundle expanded to include not just WebMagic and the Netscape server software, but many other essential tools for creating “media-rich web content”. Among those were a video tool called MovieMaker (with support for MPEG-1, QuickTime, and Cinepack) and an audio tool called SoundEditor (with support for AIFF, Sun/NeXT, and MS RIFF WAVE).

In terms of feature set, WebFORCE absolutely set the standard. Even five months later, it was referenced in a Microsoft internal exec team memo from Paul Maritz to Bill Gates, available online now because it was evidence in the U.S. Government’s anti-trust case against the company. In it, Maritz explains the gap between Unix and PCs in the web authoring space — and how it can’t be closed “until a suite similar to SGI’s WebFORCE is available on PC’s”:

High-Profile Press Event

SGI’s PR team, one of the best in the industry, pulled out all the stops. This news was clearly big enough that there was no need for pre-briefing. Instead, we would host an invite-only press event on our campus in Mountain View. In addition to the newsworthiness of an SGI product launch, we also had the big draw of the announcement of a partnership with Netscape, with Marc Andreessen agreeing to speak and do interviews.

I think we drew well over a dozen technology and business reporters. Alas, very little of the coverage we got is findable today online. Carl Furry, who was the lead from the PR team for this launch, did find this scanned piece with ComputerWorld’s coverage of the news while we compared our memories in recent days.

Historic Demo

Of course, no SGI press event would be complete without a 3D demo. Fortunately, weeks earlier, Rikk Carey, a charismatic director of engineering from the Visual Magic Division, had reached out to get me excited about a futuristic project his team had just gotten involved with, something called Virtual Reality Modeling Language (“VRML” for short). Though it was a very early-stage, grass-roots, open standard effort, I immediately saw it as an important missing piece of the WebFORCE puzzle. With the promise of bringing 3D to the web, VRML was a natural technology for SGI, the pioneer and leader in 3D computing, to embrace.

The WebFORCE launch was the first day that VRML was demoed to the press. I’m not sure what we actually demoed, but it would have been using our Open Inventor toolkit. And even though neither Marc Andreessen nor I now remember it, the ComputerWorld article linked to above says that in addition to our demo, Marc announced that Netscape Navigator 1.1 would “support transmission of three-dimensional graphics”.

Hard to believe now, but that demo and the mutual endorsement of SGI and Netscape for VRML would kickoff an industry-wide, multi-year wrestling match for control of 3D on the web. The battle would feature intense competition, awkward alliances, and multiple acquisitions. Along with SGI and Netscape, tech stalwarts Microsoft, Apple, Sun, and Sony would all become swept up in the mania. (Much more on that in future posts!)

Big Budget Ad Campaign

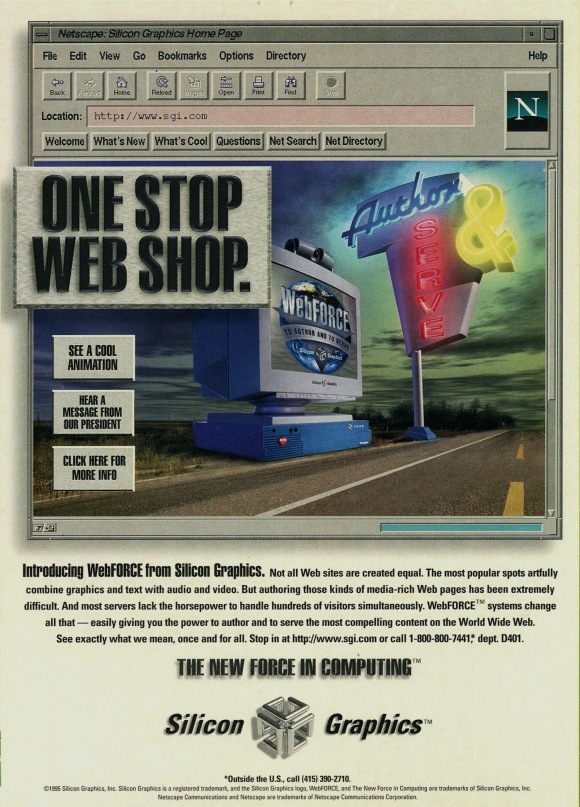

The team at Poppe Tyson, SGI’s ad agency of record, who had already blown me away by creating a killer logo for WebFORCE, did it again with what may be the very first print ads for any web product. The flagship ad, that ran for many months in publications like Wired, ComputerWorld, and since forgotten places like Interactive Age and Interactive Week, still looks great to me:

Two elements that I really love about “One Stop Web Shop” are that the primary visual is content framed within a web browser, and that the team really made this an SGI-quality ad, with multiple nods to 3D.

The secondary launch ad (shown at the top of this post) is in some ways even more remarkable. Using the web to actual sell stuff was unheard of at this point, with Amazon’s launch six months away. So for us to introduce WebFORCE as “the biggest revolution in commerce since the 800 number” was a pretty prescient claim! Readers of the Wall Street Journal got to see a full-page (but black & white) version of the ad within days of the announcement.

Over the first six months of 1995, we invested nearly $1 million to place these ads in the leading technology, business, and creative arts/new media publications. That, together with an amped up “Powered by Silicon Graphics” effort, made SGI appear to have already won the market, even before our first $10 million in sales.

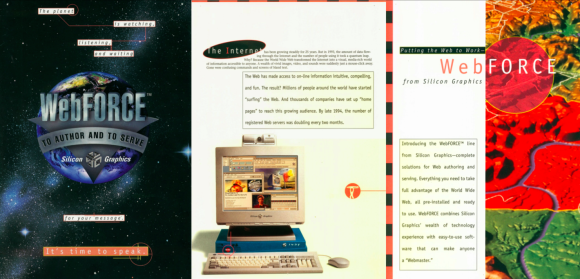

Awesome Collateral

Amongst the earliest of hires to the WebFORCE team was Kris Hagerman, who like so many from the team would go on to found and lead other startups, including BigBook, the web’s first Yellow Pages, and Affinia, a Sequoia-backed e-commerce and digital advertising pioneer. If I were the “CEO” of WebFORCE (in practice, not actual title), Kris was my “COO”.

The very first thing Kris did after coming on board was take a project that was just a notion in my head, flesh it out, and see it to completion. The challenge was to create a brochure for the product line that looked and felt more like Wired magazine and less like a corporate data sheet. Here are some scans of this really beautiful “tri-fold”:

And a Cringe-Worthy (But Highly Effective) Sales Tool

Many of you may have seen those digitized VHS tapes from the early days of the web. Well, here’s one more!

In early 1995, SGI had a 1,000-person global direct sales force. They were really awesome at selling high-performance workstations, and were becoming more comfortable selling high-performance servers and super-computers. But they did not have any experience selling software or turnkey hardware/software bundles. And, like all salespeople everywhere, they had no experience selling web authoring and serving solutions.

So, to jump start sales, we created a 10 minute sales training tape, starring me, Rob Lewis and Ciemo, along with Steffen Low, product manager for the WebFORCE servers, and Gene Trent, applied engineering for the server side of the line. In it, we explained why the web was a hot new opportunity perfectly suited to SGI (in other words, why a sales person should focus on it, or in other, other words: $). We showcased key features and key differentiators, and, given the audience, we opened and closed the narrative with references to 3D.

Like any tape from the mid-’90’s, there’s a lot to cringe at here, whether it’s the less-than-professional readings from teleprompter or the cheesy music throughout. That said, this tape was instrumental in selling tens of millions of dollars worth of workstations and servers. It turns out that though this was clearly made with the sales team as the intended audience, many sales offices would actually show this directly to prospects. But with each successive viewing, the sellers got more and more comfortable with how to pitch the WebFORCE line.

Without further ado, here for the first time on the web is “WebFORCE: To Author and To Serve”:

And that is how we launched WebFORCE!

To be continued…